Building classrooms for a better future

Children in Uganda’s refugee settlements are desperate to go to school. But the facilities can’t keep up with the demand.

In Rwamwanja – a sprawling settlement in western Uganda where nearly 70,000 refugees from DR Congo are living – classrooms are packed so full that children have to sit on the floor or gather outside trying to listen in through the door and windows.

Mr Mutabazi Lawrence is head teacher at Kyempango primary school. It has more than 3,500 children enrolled and just 16 classrooms – an average of more than 220 children per class. “The school is very congested and it means learning is not very effective,” he says.

“There are not enough classrooms, or furniture such as desks. We have seven children sharing one desk – it’s supposed to be three. Some children sit on the floor.”

According to Uganda’s Education Response Plan – the first of its kind worldwide, which was launched last year with the aim of providing quality education to 567,500 children – there is a shortage of more than 4,000 classrooms for refugees and the local host communities.

With funding from Education Cannot Wait (ECW), Save the Children is building new classrooms and latrine blocks at schools around Rwamwanja, and distributing scholastic materials like stationery and exercise books.

Construction at Kyempango is well underway and two new classrooms should be completed this month.

“We’re very excited, it will be so nice to learn in the new classroom,” says 13-year-old Francine, who gets to class as early as possible to try and ensure a seat.

“Enrolment is high but we lack the infrastructure for everyone,” says Ms. Jane Amutuhaire, the head teacher at Mahega, another local primary school where the ECW programme is constructing new facilities. The situation here is similar - with more than 2,100 pupils enrolled the school averages 217 children per class.

“Children are still studying in temporary structures,” she says. “They have one exercise book to write all their subjects. A teacher can’t take the book for marking because then the child won’t have anything to write in for their next class.”

In the mathematics class next door, the teacher hands out small kits with rulers and set squares, but there are only enough to share one between five or six children.

The lack of facilities and materials has a real impact on children’s futures. “Most of the children come here really motivated to learn,” says Ms Amutuhaire. But the long distance to walk to class and lack of materials mean they often drop out. At her primary school there are 891 children enrolled in the first year, but only 23 in the seventh and final year. “They drop out to go and work in the market to make money,” she says.

Improving the education infrastructure and providing supplies is vital for giving children a good education and keeping them in school.

But it also needs to go hand in hand with improving the quality of teaching.

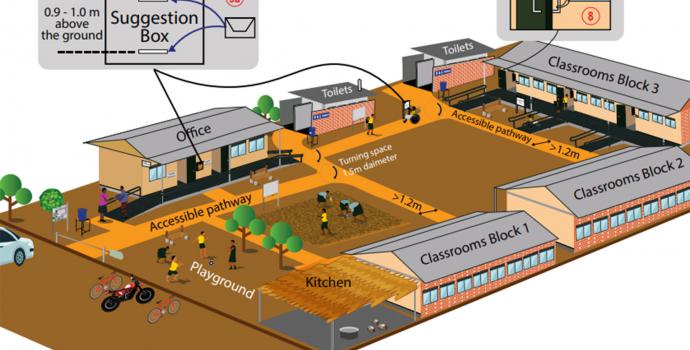

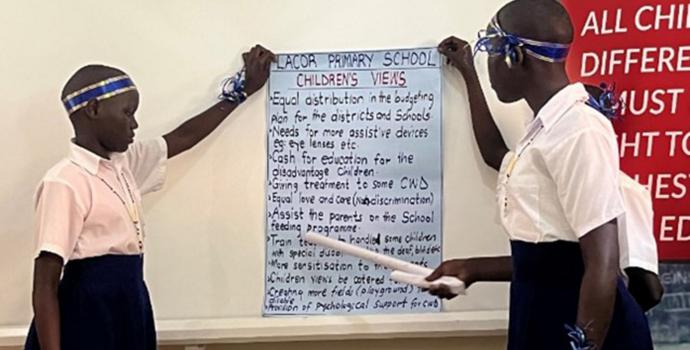

Teachers in the ECW-supported schools are receiving training on things like managing large class sizes and adapting teaching methods to make it possible for children with disabilities to learn.

Tumwine Everest is one of the Coordinating Centre Tutors (CCT) – qualified trainers employed by the government who observe classes and then offer advice and support to teachers.

“We’re seeing a big change in the teachers who are part of this ECW programme,” says Everest. “We help them with their lesson planning, teaching practices, how they assess learners. We help them design the classroom environment, so that children can learn even when the teacher is not in the class.”

In the classes at Mahega school there are now illustrated posters all over the walls. Classes are much more interactive, with learners asking questions and teachers giving immediate feedback and correction. This didn’t use to happen before.

If teachers are struggling, Everest and other CCTs arrange more intensive support and guidance through peer groups and sharing experiences.

With ECW support, children in Rwamwanja are getting a better quality education in safer new classrooms.