Gaming technology shows an exciting way to improve learning in northern Uganda

Like teenagers all over the world, Josephine doesn’t want to put the tablet down until she’s reached the next stage of the game – hopefully before her friends do.

But it’s no ordinary game. It’s been specially designed for use in Uganda’s vast refugee settlements as an interactive and fun way to improve the quality of education.

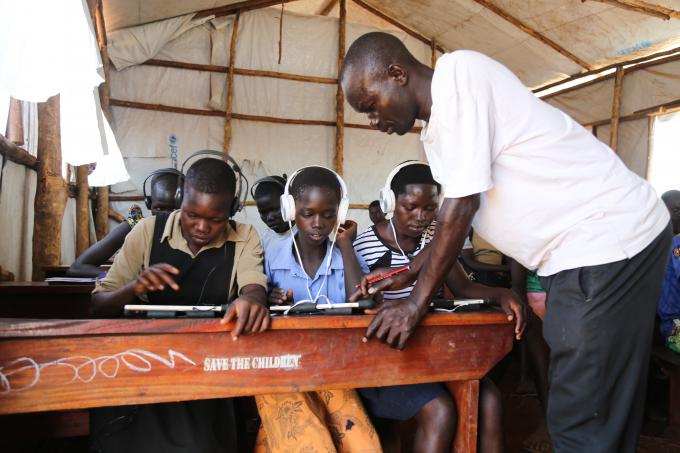

The tablets have been distributed in schools as part of an innovative project called Can’t Wait to Learn, developed by War Child Holland and being rolled out together with Save the Children, Finn Church Aid and Norwegian Refugee Council, thanks to humanitarian funding from the European Union.

The tablets are solar-powered as there is no electricity at the schools. They are loaded with two games – one to promote literacy and one for numeracy – which were co-created by a Ugandan software company in close collaboration with children themselves. Basing the games on the children’s own drawings makes them as engaging and relevant to the local context as possible.

For most of the children and teachers, it’s the first time they’ve seen or used such technology.

Josephine fled to Uganda on the back of a motorbike to escape the war that surrounded her village in South Sudan. She had dropped out of school the previous year, when she was 15 and – like many girls in her village – she got pregnant to a local man a few years older.

“While I was out of school things disappeared from my brain!” she says.

In Uganda she was able to enrol on Save the Children’s Accelerated Education Programme (AEP) which is specially designed to support older children who have missed out on school to complete their primary education. The Can’t Wait to Learn tablets have so far been distributed in 13 AEP centres in northern Uganda, as well as four in southwest Uganda for children who have fled the conflict in DR Congo.

Josephine’s daughter is now 18 months old. “My mother takes care of her while I’m in school,” she says, “and then I run home at lunchtime to breastfeed!”

It’s the first time she’s ever used a device like the tablets.

“It’s very different to when I went to school before! I like using it for English the most… it helps me correct my spelling.”

In schools where classes are often spilling out of the door with more than 200 pupils, teachers are overwhelmed so the quality of learning is often poor.

18 year-old Muja says the tablets are like having his own personal teacher. “They are better as they give one-to-one interaction. When you fail you get instructions and taken back to do it again.”

Seka, 17, says the class falls quiet when the tablets come out. “Sometimes in ordinary class it’s very noisy, so it disrupts our learning,” she says.

The tablets also mean that children in the same class can learn at their own pace – they can only move to the next level when they pick up the skills that are needed to advance.

So far about 1,200 tablets have been distributed in schools, where they are generally used in smaller classes of around 30 learners. After class the teachers take them away to safely store, recharge and use again.

When some classrooms have holes in the roof and walls, and children have to learn outside under trees, the tablets may at first seem a luxury. But Mr Leke Emmanuel, a maths teacher at Bongilo AEP centre in Palorinya settlement, says they are already having an impact. “The children concentrate more than in ordinary maths lessons. We see them greatly improve their learning.”

The tablets are low-cost and the games are designed in alignment with the Ugandan primary school curriculum, so teachers like Mr Emmanuel can easily integrate them into their normal teaching.

Even in the basic and impoverished schools in northern Uganda’s refugee settlements, Can’t Wait to Learn is showing that technology can play an important role in improving the quality of children’s learning.