Peter: A refugee, a volunteer and now manager of a children's centre

When Peter Manyhal, a 30-year-old father of five children, lost a close relative during the war in South Sudan, he didn’t want to wait for the war to claim his life as well. With his wife and children, he escaped through the border to safety in Uganda.

At the border he was taken to Rhino Camp, a large settlement which hosts more than 100,000 refugees in northern Uganda's West Nile region. After a two-week registration process, Peter was relocated to Odubu village. It is at Odubu that Peter has forged a new life – though it has not been a bed of roses.

“Coping in a new environment where you live off hand-outs and can’t support your children with the basics like milk and medical treatment was very hard for me,” he says.

Fortunately for Peter, within a few months of his arrival he applied for a volunteer job advertised by Save the Children, which had been pinned on the local noticeboard. In May 2014 he started working with Save the Children as a child protection volunteer.

“In 2015 I was promoted to Child Friendly Space facilitator and now I am the centre manager,” Peter says.

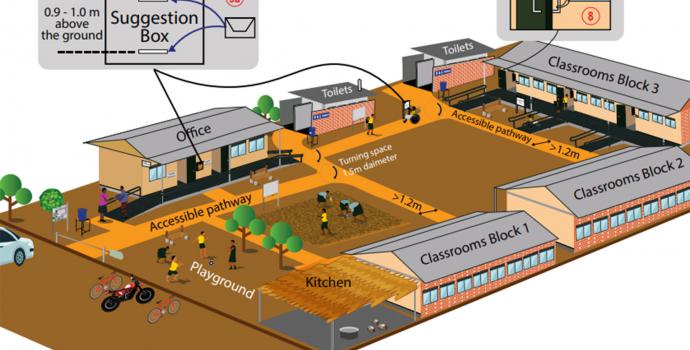

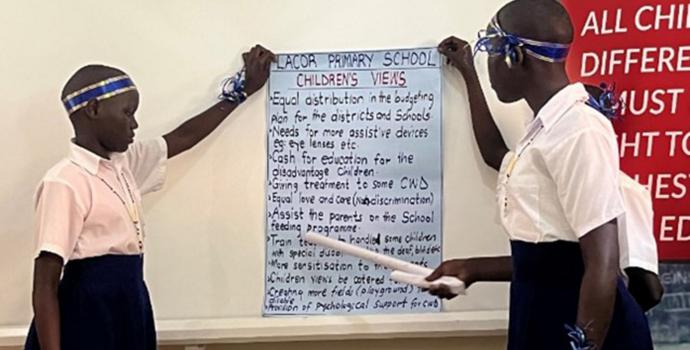

As a centre manager, Peter is charged with the responsibility of ensuring the day-to-day running of the Child Friendly Space (CFS) and Early Childhood Care & Development (ECCD) Centre, which are integrated in the same space to ensure refugee and host community children get a chance to have an early education as well as a safe space where they can play, learn and socialise. At the ECCD children aged under six years old learn basic literacy and numeracy to prepare them for primary school, while the CFS also provides services to older children.

Joseph says he finds his job fulfilling and rewarding because the centre serves as more than an education facility – it can also be a healing centre. “I have seen it first-hand when children come here traumatised by the horrific things they saw during the war or as they fled. After some time at the centre they begin to fit in, interact with others and loosen up.”

This responsibility has not come without challenges for Peter, who is managing a centre built with temporary wooden structures now eaten up by termites and in dire need of renovation. Funding for the response to one of the world's biggest refugee crises (Uganda is now home to more than 1.2 million refugees) is scarce and many structures built in the early stages of the emergency are now crumbling.

Save the Children, through funding from Save the Children Italy, is now rennovating at least 16 ECCD centres in West Nile, including the centre in Odobu village, to make them more child-friendly through building permanent structures and improving the children’s playing environment.

Joseph faces other problems too. “During this dry spell we have a faced of a shortage of water," he says. There are also other shortages: “Children’s playing materials, especially during holidays when we have many children, and essential medicine in health centres. And poverty.”

Across Uganda, 57% of refugee children are not in school, and Joseph sees the same trend in his community. “Many refugee parents have stopped bringing children to school because they can’t provide their children with a hot meal – a condition set by parents to ensure children don’t learn on empty stomachs.”

Although breakfast and lunch for children costs as much as a cup of porridge, Peter says some children come from families that have vulnerable parents. “Some parents are elderly, sick, blind, disabled and others can’t find work in the camp.”

Ultimately, Peter wishes to return to South Sudan and is optimistic the recent peace agreement signed by warring factions could hold long enough to see peace return to South Sudan. One day he hopes to resettle his family there.