Hear it from the teachers

Teachers are one of the biggest influences on a child’s life. Yet they rarely get the support or investment they need. Our new report, Hear it from the Teachers, interviews teachers in three of the world’s biggest refugee crises – Uganda, Bangladesh and Lebanon – to shed light on their experiences and the reality in classrooms.

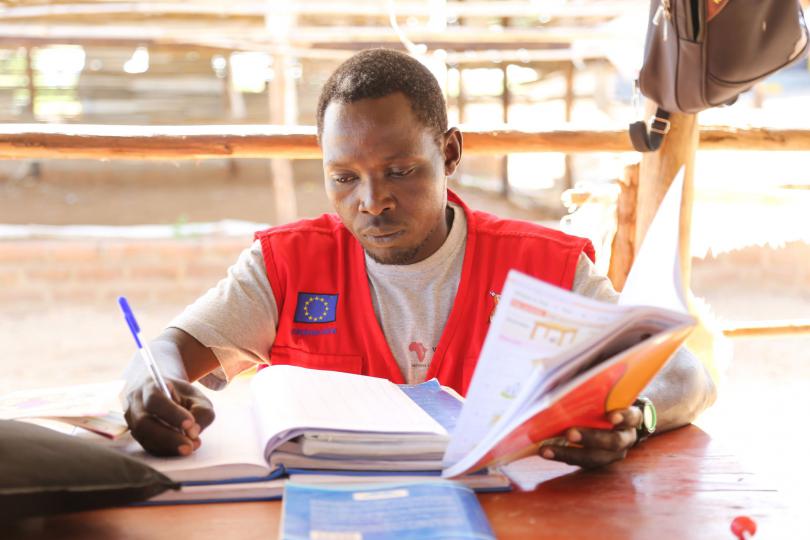

Wani David Elias, 36, teaches in Rhino refugee settlement in Uganda’s West Nile region. David knows exactly what it’s like to be a refugee child struggling to learn – he first came to Rhino as a 13-year-old fleeing the war in South Sudan. While at school he met a teacher who changed his life.

“It was here in Rhino that I decided I wanted to be a teacher,” he recalls. “I admired one of my Ugandan primary school teachers. He taught social studies and I liked the way he spoke… I would repeat and imitate his voice after class. I did a two-year teacher training course, and then my first deployment as a teacher was to the same school that he was teaching at! We got to teach together.”

After 11 years in Uganda, David returned to South Sudan in 2006 after the peace agreement was signed and continued working as a teacher there. Ten years later, in 2016, conflict flared again and he feared for his family. “We intended to send the children out of the country to safety and for us to stay. But there was too much killing. We got scared, so we came back here.”

Now back in Rhino – where more than 80,000 refugees are living – David teaches social studies and English in Save the Children’s Accelerated Education Programme (AEP). The AEP helps children aged 10-18 who had to drop out of school to get back into learning, by running a condensed curriculum which teaches the seven years of the Ugandan primary school syllabus in just three years. More than half of refugee children in Uganda are out of school.

“There are many reasons why children drop out,” says David. Many left school back in South Sudan when the fighting escalated, but lots drop out in Uganda as well. “The most common reasons are early marriage and pregnancy – mostly girls but often boys as well. Poverty is a big factor.”

Officially primary education in Uganda is free. But in reality, David says, there are many hidden costs – such as contributions to school running fees or buying books and stationery – that also force poorer children to drop out. “Children often don’t get financial support from their parents for school. They can’t afford it. Boys learn to ride a boda-boda (motorbike taxi) and then go and earn money working rather than coming to school. They look for money however they can find it.”

Around 5% of refugee children in Uganda are unaccompanied. “They stay and exist by themselves and it’s hard for them to stay in school,” says David. “Maybe their parents were killed or missing; sometimes their parents spent so much time as refugees when they were younger that they didn’t want to leave their home again this time, so stayed in South Sudan. But the younger generation wanted to come. But now they live on their own and lack basic needs like food. If they have nothing at home they won’t learn well. Their quality of learning suffers.”

“Some are traumatised after they lost their parents or other bad things happened to them. They refuse to come to school. But school is important to help them to forget the bad things.”

Uganda hosts the largest number of refugees in Africa and the influx has put enormous strain on local resources. There are not enough schools and classrooms for everyone. David says the local primary school only has capacity to run three grades of primary education rather than the full seven. “After they finish P3 (primary grade 3), when they are about age 9 or 10, the nearest school is very far away, about 5kms walk. They have to set off from sunrise to sunset, sometimes with no food and water. Many drop out after P3 and stay home instead.”

Primary schools in Uganda’s refugee settlements have an average of 85 pupils for every teacher – more than double the national average. To meet government standards just for the currently enrolled pupils alone, an estimated 1,757 additional teachers would be needed. However, employing new teachers is a challenge. David qualified as a teacher while in Uganda so is able to work here, but many refugee teachers only have qualifications from their home country, which are not recognized by the Ugandan government. Setting up an accelerated approach to re-train and register these teachers to work in schools in Uganda would help rapidly reduce the pupil-teacher ratio and greatly improve learning.

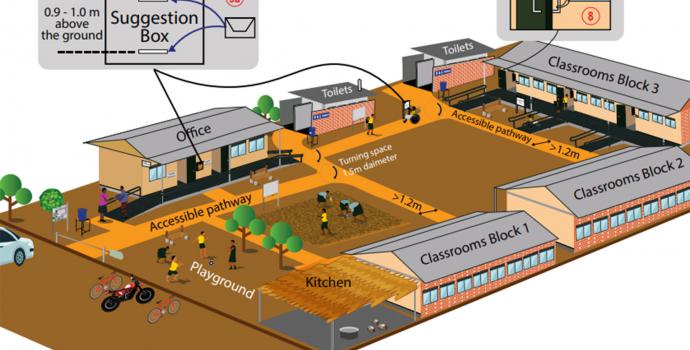

The Hear it from the Teachers report also calls on host countries, donors and humanitarian agencies to prioritize steps including training teachers in skills such as psychosocial support; reducing class sizes and providing adequate school structures; paying teachers a decent wage; and better harnessing the power of technology to improve the quality of education.

“When the refugee children came they thought they would go home to South Sudan quickly,” says David. “They thought they wouldn’t be here long enough to need to learn. But the war went on and they realise they will be here longer, and they realise the importance of education. The first week when they join their behaviour is often not good, but with time it quickly starts changing.

“Our country is our home, and once there is peace we can go back. That’s why it’s so important to invest in education. In future, when there is peace, the children will use the knowledge and skills they acquire here to develop our country.”

NGOs call on the world to support Uganda's new Education Response Plan